“I’m enjoying the fiestas and gradually working towards a film documentary”

A village in Mexico and the Holy Week, a hit-and-run car accident, and a tequila-drinking police chief – and a film team from Göttingen at the heart of it all. Six binder files and reels and reels of film material tell the adventure of an expedition to Mexico 30 years ago. With the “unearthing” of an ethnological film treasure, the preliminary end of the tale can be told in 2018.

A contribution by Miriam Reiche and Bastian Drees to the 2018 World Day for Audiovisual Heritage.

diesen Beitrag auf Deutsch lesen(Text in italic indicates translations of direct quotations from the project files V 2588 Mexiko (Engelbrecht) regarding the Mexico expedition)

A postcard and an accident

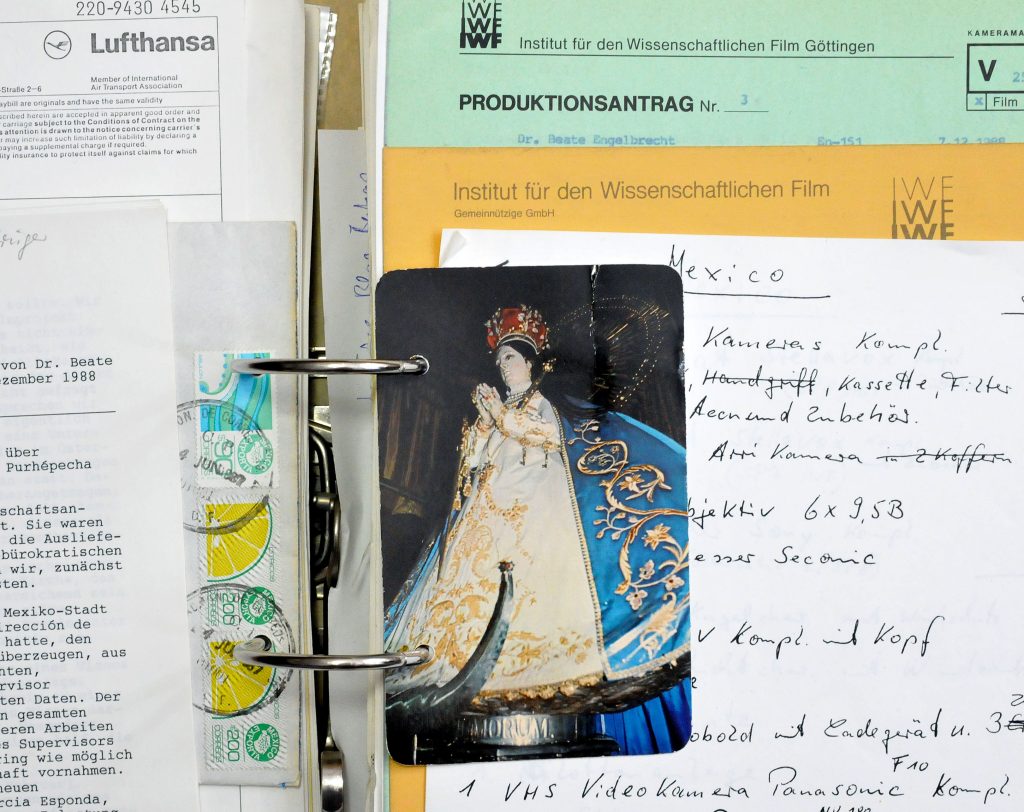

On 21 May 1987, Dr. Beate Engelbrecht, ethnology specialist at the Institute of Scientific Film (IWF), wrote a postcard from Pátzcuaro, Mexico, to cameraman Manfred Krüger: Dear Manfred, May the Virgin of Health be with us on all our journeys. I’m enjoying the freshly made tortillas with beans and a bit of chili. I’m enjoying the fiestas and gradually working towards a film documentary … Best wishes, Beate

Almost exactly two years later, on 13 April 1989, Ruth Merkel, a representative from the German Embassy in Mexico, wrote a memo with the subject line Car accident: Dr. Engelbrecht and Herr Krüger from the Institute of Scientific Film, Göttingen, who are in Michoacán to make a film, had a car accident today.

Both documents – the postcard and the memo – can be found in file En-005 03 of the IWF project files V 2588 Mexiko (Engelbrecht). Whether it was the Virgin of Health that stood by the film team of Engelbrecht and Krüger is not recorded. What is certain, however, is that both were only slightly injured, even though their VW bus was hurtled through the air, rolled over, and was a complete write-off.

The DFG application and the purpose of the expedition

Back in January 1988, Beate Engelbrecht applied for financial support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) for a “Film Documentation ‘Religious Life of the Purhépecha – Michoacán, Mexico’, continuation of Project En 174/1-1 – II A 5, and ‘The Documentation of Traditional Handicraft Techniques in Michoacán, Mexico’.”

The purpose of the trip was to make a documentary film on particular religious rituals and various handicrafts of the Purhépecha (Michoacán). This was to include a documentary of the religious cycle from Candlemas to Easter, as celebrated in Patamban, a Purhépecha village in the Sierra Purhépecha, Michoacán. The climax of the religious cycle would therefore be the Semana Santa (Holy Week) leading up to Easter. This was recorded in the film “Semana Santa – The Holy Week in Patamban”, which was based on nine years of research in Patamban. The Semana Santa was observed and chronicled twice before shooting started. The film team consisted of two people: camera (Manfred Krüger), and direction and sound (Beate Engelbrecht).

The DFG approved the proposal, and the expedition was co-financed in almost equal parts by the IWF and the DFG. Just before New Year’s Eve 1988, the film crew began the journey from Göttingen to Patamban, Mexico.

Patamban, Michoacán, Mexico

Since most of the shooting was planned to take place in Patamban, particularly the documentation of religious life, the village served as the base for the expedition as a whole. The village of Patamban lies in the western Sierra Purhépecha in the Mexican state of Michoacán. Politically, it belongs to the Tenencia of Tangancícuaro, but is independent regarding church matters. Patamban is a relatively large village with a population of three to four thousand that primarily survives on agriculture and pottery.

Upon their arrival in Mexico, the film crew was received by representatives from the German embassy, but, for political-bureaucratic reasons, subsequently had to wait for the release of the filming equipment from customs. It was then decided to first pick up and test the VW bus that had been ordered in Puebla. While the VW bus would perform well for the first few months, it would not survive to see the end of the expedition.

Once the equipment had been handed over from customs, and the film crew had been assigned a minder from the Mexican government, which was a difficult ordeal for the film team, as it seemed that he perceived his only task as pulling money out of the [film team’s] pockets, they set out for Patamban, Michoacán, at the beginning of January 1989.

Shooting the film – in close cooperation with the villagers

Having arrived in Patamban, the film crew set up and spoke with the Cabildos, the oldest people in the village, about the planned film project. The Cabildos, as representatives of the villagers, endorsed the project, in which they saw support for their struggles to revive their traditions, above all their Easter ritual.

The Religious Cycle from Candlemas to Easter incorporates many additional rites and traditions in addition to the two in the title, including Carnival as well as the Last Supper in particular. Shooting began on 2 February with the ceremonies surrounding the Purification of Mary. These are documented in Film C-1895, “C-1895 „Candlemas at Patamban, Michoacán, Mexico”. Next, shooting for the topic area of Carnival (6-8 February) was done (see Film C-13228 “Carnival in Patamban, Michoacán, Mexico, which was then followed by shooting of the ceremonies surrounding Jesus of Nazareth. The latter actually began with Ash Wednesday and ended with Easter.

As a result of the complex and diverse rituals, which sometimes took place simultaneously in different locations in the village, the film team of Engelbrecht/Krüger was reliant on good cooperation with the villagers. Because the villagers were largely positive about the film project, the team occasionally without prompting, was provided with information or even called over to particular events. In the course of their stay in Patamban, this cooperation intensified, such that by the time the last shots were recorded, there was close cooperation between the filmed and the film team.

E-3135 Semana Santa – Holy Week in Patamban

After a few shootings of traditional handicraft in other locations, to bridge a longer shooting break in Patamban, intensive preparation for the documentation of Semana Santa began in mid-March. Additional lighting had to be installed in the church, as the 16mm film required a brighter setting. The film crew donated two chandeliers to the parish, to which additional spotlights were attached. Another challenge was the length of the procession. Since a roll of 16mm film lasted only about 10 minutes, pauses in the filming had to be planned to swap cassettes. To be as mobile as possible, the film was almost completely shot from the shoulder. Ms Engelbrecht took on the sound recording and stood literally shoulder-to-shoulder with the cameraman. This allowed her to point out important activities during the procession to him. It was, however, unpleasant for the film team and the villagers that the minder “always butted in, instead of sitting still somewhere.”

Above all, Holy Week in Patamban consisted of a “Passion Play”, which lasted for a week. In the IWF files, Beate Engelbrecht noted the following about the filming: This lasted eight days. A major part of the film was shot at night, both in the church as well as outside. The Easter festival in Patamban is an especially complex celebration, in which completely different rituals intermingle. Due to the complexity of the celebration and the numerous parallel ceremonies taking place at the same time, it was only possible to document a selection of the celebration. We therefore focused on the main activities in and around the church. Wherever possible, we endeavoured to include side activities, such as changing the clothes of a saint, vigils for a saint, or the coming and going of a carguero.

After the end of the Holy Week, the work in Patamban was finished and once again the film crew climbed into their trusty VW bus and made their way to new filming locations, to record the everyday life and work of a family of weavers (the weaver ladies actually enjoyed it) and other handicraft activities. For a good three weeks, the VW bus ferried around the film team and their equipment, then itself came to the end of the road. The last 40 meters of its service it travelled by air.

Tequila with the chief of police and a lost pair of glasses: the car accident

On 13 April 1989, Manfred Krüger found himself behind the wheel of the VW bus on the way from Cheran back to Patamban. As he was turning onto an unpaved road an accident occurred, which Frau Engelbrecht documented in the accident report: At this moment, a bus drove into us from behind … Our VW bus was hurtled through the air about 40 m. Then it rolled over once, right over a little bridge, whose guideposts were destroyed by the car … Luckily, we did not lose consciousness, nor were we seriously injured. But the car was completely written off.

The equipment had also taken a knock. The camera case itself was severely distorted … Some of our metal chests were badly dented, some of the film canisters were crushed. Frau Engelbrecht also lost her glasses. After the first moments of shock passed, the bus driver got back behind the wheel and left the scene in a case of hit-and-run. A bit later, the local police arrived on the scene, but, due to a lack of jurisdiction, there was little they could do. Instead, the local police … pursued the fleeing bus.

After the full recovery of the film team, a bureaucratic odyssey through the police stations, the German embassy, insurance companies and the bus company followed, chasing the question of how the damages would be replaced. The insurance agent quashed all hopes of a straightforward solution with the observation that meanwhile, the director of the bus company had already gone out drinking tequila with the chief of police. Even by the end of the expedition, no solution could be found, and Frau Engelbrecht resignedly notified the DFG: Mr Krüger and Ms Engelbrecht unfortunately could not do anything more in this case.

“It has become a historical document” – A film returns

Three years later, in August 1992, a contribution from Beate Engelbrecht was published on page 7 of IWF-aktuell No. 21: “Semana Santa – Ein Film kehrt zurück (Semana Santa – A Film returns”). In this article, she discussed the return of the “Semana Santa” film to Patamban and its significance for the inhabitants there as a piece of their cultural memory.

When Ms Engelbrecht returned for the Holy Week in Patamban in 1990, she discovered that since then, the “Dramaturg of Holy Week”, Antonio Clemente, had passed away, leaving “a huge knowledge gap, that clearly was not easy to fill.” In his youth (before the Mexican Revolution!), he had accompanied a priest, and in doing so learned the fundamentals of the passion play. Later, in the 1950s, he and two other people (including a sculptor who specialised in figures of the saints) had put on a new staging of Holy Week. Antonio Clemente had “overseen the passion play for decades” and was the only one “who knew everything.” It was against this backdrop that the raw, unedited footage took on special meaning for the villagers of Patamban, and why even today there is a special interest in this film. “The film already appeared to have become a historical document at that time.”

In December of the following year, Ms Engelbrecht and Mr Krüger travelled “once again to Patamban, to premier the completed film.” The first screening of the film took place on the village plaza, “so that all the villagers could take part in it.” The film fascinated the audience for a long time, because hardly anyone had ever experienced the fiesta in this way. For Ms Engelbrecht it became clear that “the ‘return’ of the film led to a completely new collaborative relationship, this time initiated by the village itself to us, the filmmakers.”

And today?

It was in 1979 that Beate Engelbrecht first travelled to Patamban, and since then she has returned almost every year either to Mexico or to the “outpost in Florida”. Her Mexico research and film work have spanned the majority of her life. Even today her film work (“no trips without a video camera!”) serves to develop new perspectives on ethnographic film work and new ideas, and to pass these on to young people. Still, there is one point that leaves her at a loss. “Since the closing of the IWF, there is no place where ethnographic films produced in Germany are collected and preserved. If you think about the topic of cultural heritage and what film can do for that, this is particularly sad.”

Since 2012, an unexplored treasure has patiently slumbered in the closed stacks of TIB, which took over the IWF film archive that year

Films are a fragile cultural good. Film copies were intended to be used, and not to be stored for all eternity. Cellulose acetate, the film base, is susceptible to “vinegar syndrome”, a problem also encountered by IWF films. Time is short, and the Ethnological Collection is being digitised within the DELFT (Digitisation of EthnoLogical Films) project and made available in the AV-Portal, which is a first, important step.

The Ethnological Collection comprises almost 2,000 films, including some up to 100 years old, with most recent films, such as Beate Engelbrecht’s Mexico film, dating from 1992.

A “film”, however, not only means the physical copy itself – often there exists a range of other material as well that ,for example, documents the production and distribution of the film. Such material also exists for the Ethnological Collection, including photos and slides of expeditions, corresponding audiotape, and booklets published for every film. One special aspect involves the editorial and production files of the IWF. These files are a piece of the institute’s history and they provide a deeper view into the context concerning the origins of the film, revealing just how much passion and effort was put into every individual film. For this reason, we have decided to digitalise these supplemental film documents within the DELFT project as well, and in so doing prepare the path for their future accessibility.

Information does not remain accessible

To preserve this type of film, which in the post-digitalisation future will involve preserving the analogue original and the digital copy, appropriate preservation strategies must be developed in light of their different characteristics. As such, a preservation strategy is not a static situation, but a dynamic process in which constant development must take place and must continuously be monitored.

With the digitalisation of the Ethnological Film Collection, TIB is taking responsibility for the filmed works of the IWF. To comprehensively preserve the cultural goods, in line with Beate Engelbrecht, it is not enough to take into account only the digitalisation and archiving of works; preservation is only achieved once it is combined with indexing and provision, creating access to these works.

We would like to thank Beate Engelbrecht for her support and a lot of additional information that goes beyond the content of the file.

About Dr. Beate Engelbrecht:

Dr. Beate Engelbrecht studied Ethnology, Sociology and National Economics at the University of Basel, where she completed her doctorate on the topic of “Töpferinnen in Mexiko. Entwicklungsethnologische Untersuchungen zur Produktion und Vermarktung der Töpferei von Patamban und Tzintzuntzan, Michoacán, Westmexiko.“ (Ceramic workers in Mexico: Development-ethnographic Studies on the Production and Marketing of Pottery in Patamban and Tzintzuntzan, Michoacán, western Mexico) in 1985. From 1985 to 2012, she worked at the IWF as an ethnographic filmmaker and headed the Culture and Society Section and from 2002 to 2008 the Transfer Business Unit. In 1993, she founded the Göttingen International Ethnographic Film Festival (GIEFF).

You can find Beate Engelbrecht’s films in the TIB AV-Portal here.

... arbeitet im Kompetenzzentrum für nicht-textuelle Materialien (KNM).

Eine Antwort auf ““I’m enjoying the fiestas and gradually working towards a film documentary””