ConfIDent’s predatory conference identification workflow

One of our main goals with ConfIDent is to build a registry of academic events without listing those that are predatory. This blog article describes the assessment workflow that is employed to achieve this and discusses its limitations.

Predatory conferences and conference quality

This year’s interacademy partnership (iap) report „Combatting Predatory Academic Journals and Conferences“ provides a useful definition of what is meant by predatory conferences:

An important aspect highlighted by this report is that quality with regards to conferences is best understood as a spectrum with extreme, predatory cases on one and high quality cases on the other side – and many shades of grey in between. With ConfIDent, we want to exclude the clearly predatory cases. The workflow presented here was developed to provide a high degree of certainty about whether an event is to be considered predatory or not. Hence, we don’t make statements about an event’s “shade of grey” and instead only determine in a binary fashion if events should be considered explicitly as predatory.

One important thing to note: By quality we do not exclusively mean “scientific quality” of the research presented at conferences (i.e. validity, reliability, reproducibility, methodological rigor, relevance of research question, impact, etc.). Quality with regards to academic events and in the context of this workflow should be understood more generally as the level of satisfaction of researchers’ needs they intend to satisfy with their conference participation (e.g. networking, learning, gaining reputation, receiving feedback, publishing research, etc.). There are plenty of examples where good science is presented and successful researchers participate at predatory conferences. Still, being predatory and attracting poor quality research are likely correlated.

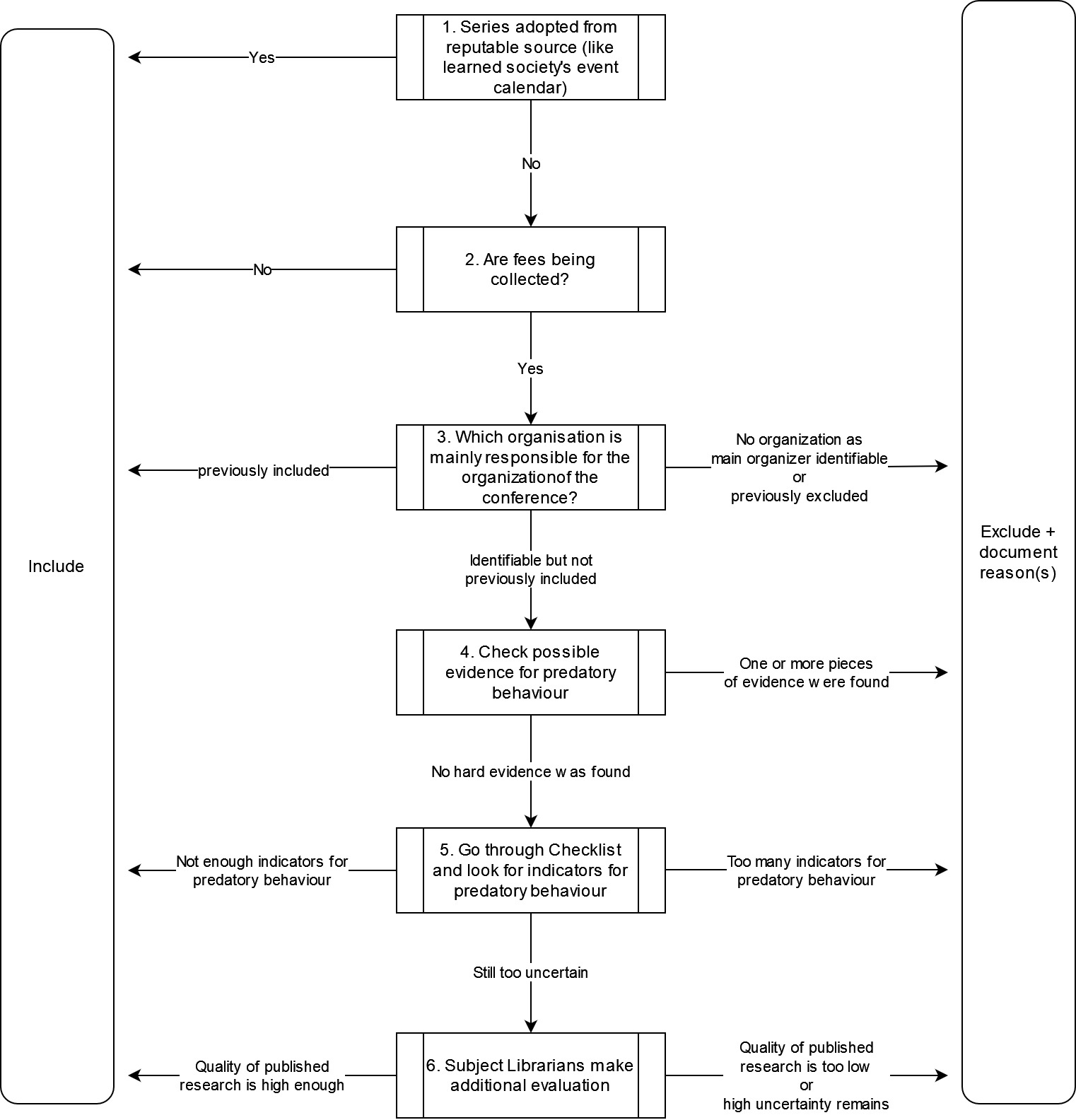

Current predatory conference identification workflow

The workflow consists of multiple steps. The effort needed to complete a step tends to increase with each step. Not all steps necessarily need to be completed to reach a decision. On the contrary; by ordering the steps in such a fashion we hope to be able to arrive at a quick indexing decision with the first step(s) and thus save effort. The certainty of whether to include the investigated event or not should increase with the number of steps taken until the investigator is certain enough to make the decision.

The workflow is designed for metadata curators who are mostly unfamiliar with the events’ fields of research. Because of this we try to minimize the assessment of the event’s scientific quality in the workflow. Experienced researchers trained in the specific academic field relevant to the event probably will look at the event’s scientific quality earlier in their evaluation. Severe lack of scientific quality of published and/ or presented research is an insightful indicator for predatory behavior. It should raise concerns about the trustworthiness of the review process and therefore the event.

Step 1: Sources

In the ConfIDent project we frequently seek out secondary sources to first of all learn which academic events exist in a field. We usually base our curation efforts on these sources. They for example include event calendars or recommendations of learned societies, rankings produced by credible organizations or rankings that are well-established as an assessment tool in the community and are based on publication metrics. In these cases, where we have good reason to trust the secondary source to only include trustworthy events, the mentioned events are indexed and the workflow is completed after the first step.

Step 2: Collection of fees

Organizers of predatory conferences have one primary goal: Monetary gains. Legitimate organizers like learned societies of course may also pursue this goal, since it often represents one their major methods of generating income (see for example IEEE’s or ACM’s annual reports). However, we assume that providing a high quality conference at least is equally important to them. Additionally, they are not as tempted to sacrifice the conference’s quality in order to reduce costs because any profit made from the conference is funneled back into the organization where it is used to provide other services to the community (or build reserves). No individuals should be able to enrich themselves through conference fees in the case of traditionally organized learned societies. This is often legally insured by learned societies legal status of being non-for-profit. Depending on the country, non-profit organizations take on different forms of legal entities: tax-exempt, Verein, etc.). In contrast, predatory conference organizers always act with their ultimate goal in mind to enrich themselves (personally).

Based on these considerations we assume that if an event does not collect any fees, it is not predatory because predatory organizers don’t have any incentive to organize such events. We therefore include free of charge events without any further checks.

Step 3: Identify organizer

If the event in question was picked up from anywhere else by a curator or came through any other channel like a non-curator user and fees are involved, the organizer of the event needs to be investigated. The organizer is considered as an organization that carries the main responsibility for the event. This in particular means the legal entity that is handling the financials, i.e. which is collecting the fees and paying for the event’s expenses. It is rarely the case – at least with somewhat larger events like conferences – that the event is exclusively organized by individuals of the scientific community. Usually, a university, institute, learned society, etc. takes on responsibility for the conference and communicates its involvement in the event. Even in those cases where organizations appear to play an insignificant to no role in the conference, it is highly unlikely that for example the general chair’s personal bank account is used for transactions. As a guiding principle in this step we “follow the money”.

Unfortunately, even with trustworthy organizers, it is often not easy to find out which entity exactly is responsible for the financial side of the organization. Transparency for predatory organizers however is something they consciously try to avoid. Sometimes identifying any organization at all is impossible. They often try to appear as community-driven as possible by highlighting individuals (mostly researchers occupying positions like chairs etc.) as the ones responsible for the organization of an event. If it is therefore impossible to identify any organization responsible we assume that the organization doesn’t want to be identified and has something to hide or that individuals are benefitting off the fees. Hence, we don’t include the conference.

Organizations that were previously found to be involved in the organization of predatory conferences, i.e. show obvious (signs of) predatory behavior (step 4 and 5), are noted on an internal list of exclusions. Those organizers that already had one of their events successfully pass through the QA workflow will be noted on an internal list of inclusions. If the organizer in question appears on one of those lists, the investigation ends and the corresponding action will be taken.

Step 4: Examination of behavior

Since we have identified an agent conducting the event’s organization in the previous step, we can now examine the agent’s behavior and hopefully determine whether its behavior should be considered predatory or not. We understand predatory behavior as consciously making statements about one’s event that are untrue, thereby deceiving potential participants.

Features of academic events that are prone to being lied about by predatory organizers are exactly those that researchers base their participation decision on, often indicate an event’s quality and involve a lot of effort and costs. As mentioned in Step 2, predatory organizers try to minimize costs as much as possible while maximizing their event’s attractiveness but crucially don’t refrain from fraudulent methods to achieve this. Examples for such features are the legal status of the organizing entity (non-for-profit), affiliations with other organizations (sponsors, co-organizers, publishers, etc.), affiliations with individual researchers (committee members, board members, keynote speakers, etc.), review process/ editorial process, proceedings publication, indexing of proceedings, program and covered topics, event size and event location. During this step it is relevant which event features an organizer claims apply to his event and whether the event does in fact exhibit those features in reality. Therefore, although for example not conducting a peer review process might influence the event’s scientific quality negatively, the lack thereof doesn’t constitute predatory behavior as long as the opposite is not claimed.

Now, with these features in mind our first point of entry into this investigation step is the event’s own website. There we can find the organizer’s claims with regards to these features. During this part of the investigation we try to find instances where it is evident that the organizer’s claims are false, i.e. where the claims don’t fit the facts or where he contradicts himself. In our experience the following claims lend themselves well to being investigated in a desk-research manner and – besides affiliations – can be checked with publicly available information on the web. The list is certainly not exhaustive. The more effort one is willing to spend the more lines of investigation will open up. We are of course limited in the time we are able to spend on one investigation.

Obfuscation of profiteers

- The claim: There are different legal entities involved in the event. They appear to be separate from each other, only linked by their shared business. Typically one entity might be mainly responsible for the academic content. Another acts as the local organizer, dealing with booking the hotel room etc.. And one entity often acts as the publisher of the conference proceedings.

- Reality: In fact there is only one (legal) entity registered that is behind all these apparently different agents, thereby intentionally obfuscating who is really behind the organization and profiting from it.

- Evidence: Websites imprints or contact addresses of apparent different legal entities point to the same address. Or only one or fewer than claimed legal entities are actually registered in the country they are supposed to reside in. In more complicated cases there are separate legal entities that all link back to one or the same few individuals which in itself is not necessarily deceptive as long as they didn’t claim the contrary. But this should raise a lot of suspicion.

Non-profit nature of organizer

- Claim: The organizer is incorporated as a non-profit entity. Thus, all income generated by the event is used to cover its costs and/or will be reinvested into the organization, ultimately serving the community.

- Reality: The organizer is not legally recognized as a non-profit entity.

- Evidence: Most countries assign a certain legal status or legal form to non-for-profit organizations that usually come with benefits like being exempt from taxes but also involve duties like filing and publishing annual reports. This wikipedia page provides a helpful overview about where to look up legal entities in most countries. The organizing organization does not have such a status.

Stand-alone events

- Claim: The organizer hosts several conferences from different fields and with different topics at the same time. They are marketed as stand-alone events. They are seemingly unrelated or merely co-located. Each having their own committee members, own websites, sometimes their own publications, etc. They are not marketed as interdisciplinary.

- Reality: There is in fact only one event where participants of each stand-alone event participate together.

- Evidence: The conference program is the same for all those conferences. Each conference now merely appears as a session or there is no structure left allowing to identify which talk belongs to which conference supposedly. There are usually not enough talks even if the organizer wanted to host stand-alone events. They have the same keynote speakers. One proceedings covers all events or several proceedings for each event are published with only a handful of contributions. The same photos used multiple times is an indicator too.

Location

- Claim: The conference is held in person at a physical location. A city is already chosen (and marketed). It appears as the venue will be announced soon.

- Reality: The conference is held completely online.

- Evidence: Up until the start of the conference no information about any venue is communicated on the website. After the conference only screenshots of video calls are published. Sometimes youtube videos of recorded video call can be found.

Indexed publications

- Claim: The published proceedings are being indexed by popular indexing services like Scopus or Web of Science.

- Reality: They are not indexed at all or proceedings of previous years are not findable anymore in the index.

- Evidence: Not being able to find the proceedings in one of the mentioned indexing services.

Affiliations

- Claim: The conference is affiliated with a range of prestigious organizations and individual researchers. Organizations might take on the role of sponsors, supporters, co-organizers, etc.. Individuals’ roles are members of boards or committees, chairs, key-note speakers, etc.

- Reality: The mentioned organizations or individuals are not affiliated with the conference. The conference might be unknown to them.

- Evidence: The lack of communication of the mentioned organizations and individuals about their involvement in the conference can be a first sign. However, certainty in this regard can only be achieved by contacting said organizations and individuals and asking for a confirmation of their involvement.

If any one of those points revealed that the organizer made a deceptively false claim, the conference will not be included in ConfIDent, nor will other conferences from the organizer. We assume that the organizer acted in bad faith and is not trustworthy.

Step 5: Further indicators for predatory behavior

If no concrete evidence for predatory behavior was found during step 4, we will look at the conference even more thoroughly. During the course of the project we came across many features of academic events that can be interpreted as indicators for predatory behavior. It is important to note that non-predatory conferences also may exhibit such features but in total should do so less. Therefore we clearly distinguish between the methodology of step 4 and step 5. In contrast to step 4 exhibiting such features does not immediately constitute predatory behavior, hence the term “evidence” was used in step 4. They are better understood as indicators or signs for predatory behavior and have to be looked at in their sum.

This checklist serves as a basis for a somewhat structured approach during this step. It is based on the advice of many other people working on the problem and our own experience. It will be continuously amended and improved. Since a lot of sources are written for researchers and not for librarians or they involve lengthy review processes that cannot be integrated into the efficient operation of a service, some of the indicators are not viable for us to check. Those are marked in the column “Difficult for curators to assess”.

This step is based on a collection of indicators. If too many indicators of predatory behavior are identified, the conference will not be included. We have not concluded on any threshold of indicators yet. We hope to, after having gathered more experience in this regard, to establish an appropriate limit. This step in particular comes down to the criteria-supported expertise of the investigator. As with every other step, we try to be as objective as possible by documenting the reason(s) should a conference be excluded.

Step 6: Evaluation by subject librarian

If after all those five steps the investigator is still uncertain about including or excluding the conference, subject librarians will be involved who have in addition to their librarian expertise a strong academic background in the academic subject they are responsible for. They will look into the scientific quality of the conference’s output, similarly to when they decide whether to purchase for example a new journal for the library. They are also better able to judge the significance of the conference’s affiliations because of their familiarity with the subject field. They possess the kind of implicit field knowledge that allows a deeper, content related assessment of a conference. If they too remain uncertain whether the conference is trustworthy, the conference will not be included.

Limitations and responsibility of attendance decision

While we hope to succeed in listing only non-predatory conferences, even an elaborate process like the one described is no guarantee. Given the opaque nature of conference organization and the peer review process in particular, we cannot give complete guarantees, but only an approximation to a predatory-free conference register..

However, we have to emphasize that the last responsibility to make a judgement always lies with the researcher who thinks about attending a conference. They have to decide for her-/himself whether the conference in question is acting ethically (enough) and exhibits an acceptable level of scientific quality. Indeed the interacademy partnership (iap) correctly recommends to not „rely on imperfect ‘watch’ or ‘safe’ lists“ [iap 2022:77]. Researchers should not base their participation decision entirely on a conference being indexed in ConfIDent or not. Nevertheless, we believe that by moderating the content of the ConfIDent platform we provide valuable support for their decision-making.

Future QA Workflow

In the future, if users are convinced that an event series that is listed in ConfIDent should be considered predatory, they will have the option to flag it and send a short explanation as to why they think so. This will lead to further analysis and a re-evaluation. Personal experience from somebody who for example communicated with the organizers, experienced their review process or even attended one of their events themselves is of course very valuable and often more insightful than an investigation limited to available information online. In case an event is rejected and the event was entered by a user, we intend to inform the user about the reasons for the rejection.

To support curators with their assessment and to prioritize new entries, the integration of an automated pre-check is planned, in which primarily completeness and plausibility of the available metadata of new entries in ConfIDent will be checked. This pre-check will provide fundamental information about metadata quality, which in turn may give reason for further, intellectual review. Maybe we will even be able to operationalize some indicators in a way that a simple algorithm can detect them: e.g. a good and easily quantifiable indicator could be the time span between submission and notification date. A very short time span may indicate the absence of a peer review process. However, most indicators of predatory behavior are difficult to objectify, as they only reveal themselves after close investigations and are less quantifiable. Also, limited to our own metadata, fact-checking as described in Step 4 of the QA process can probably never be conducted by an algorithm.

Norms of transparency

The identification of predatory conferences could be a lot simpler and maybe even unnecessary if academic conference organizers would be more transparent with regards to the conference organization. Predatory conference organizers evidently thrive in an environment where transparency is not the norm. Making it the norm to clearly indicate which organization exactly is in charge of the money and maybe even what the money is used for (for example supporting other services of the non-profit) already would be of great help. Another key aspect where increased transparency as a norm would make it harder for predatory conferences to attract researchers is the peer review process [iap 2022: 80]. Claiming to conduct a peer review process or at least an editorial process but not doing so is probably one of the most common predatory practices and the one with the worst impact on conference quality. Unfortunately, it is generally very difficult to test this claim. With the ConfIDent plattform we hope to contribute to this normative change in academia by making the relevant information about conferences more easily accessible in a structured manner. Of course significant change is only achievable if organizers themselves work towards more transparency.

Research Assistant in the Lab Non-Textual Materials at TIB

Eine Antwort auf “ConfIDent’s predatory conference identification workflow”